“Remind me of your surname again?” she said, very politely, as it rarely appears on my social media.

“Hussain,” I quickly remarked through a warm smile, proudly, pre-empting the kind of response that recipients so often give when they hear my name. It’s impossible to blame them. My appearance portrays a young, female with distinctly Caucasian features and so to receive somewhat of a startled, hesitant, sometimes even apologetic response is pretty ordinary for me.

Yet, that has been a reality for a significant portion of my life. I grew up in the United Kingdom with an English mother and middle-eastern (though British national) father and the pleasantries surrounding my surname have ranged from light-hearted humour to remarks that are deeply, deeply offensive.

The pleasantries surrounding my surname have ranged from light-hearted humour to remarks that are deeply, deeply offensive.

Crossing the border of the United States in the last 10 years, especially in the last three as I finish my studies here, has been another tale to tell. Frequently, nonetheless, I have been the subject of random searches, I got used to being identified and categorized due to my last name. On other occasions, there was no bat of an eyelid.

It truly doesn’t bother me so much. On many occasions, it has left me the recipient of the threat of stereotypes. Most of the questions about my heritage are sincere and inquisitive, and I find myself more than happy to share or be searched as I have nothing to hide. It quickly becomes a point of interest, and there is much in my heritage to be proud of.

However, I do think it is worth considering: Those who hold preconceived beliefs and ideas about the recipients deny their access to equal opportunities, which results in the disqualification or the false assumption of others. It is not the explicit biases that are hard to address but rather the hidden ones, the ones that creep up and influence the conversation.

It is not the explicit biases that are hard to address but rather the hidden ones.

Often, these implicit biases cause people to attribute values and characteristics, even actions, to an entire group of people. They can make people feel misunderstood and counteract connection.

Yet, they are not always negative. Often biases are simply the filter by which your brain processes information, formed by what you believe based on experience (nature, or nurture). Left unnoticed, our biases disrupt, but appropriately addressed, they keep us curious, informed and suitably empathetic.

Here are a few tips to help us address them:

1. Biases are normal

Though commonly misconstrued, biases do not equal prejudice, racism or even discrimination. While people might like to think that they are not susceptible to these biases, the reality is everyone engages with them on some level.

Though commonly misconstrued, biases do not equal prejudice, racism or even discrimination.

Biases indicate that the human brain is functioning correctly in filtering experiential and social information according to beliefs. It is important to remember that everyone has defining moments in their life that have shaped, influenced and changed them in some way and these facets will be brought to the table no matter what.

2. Identify your filters

We are wired to recognize patterns and associations. Spend some time thinking about the environment you were brought up in, the parenting style you saw (or did not see), how you make choices and the patterns of consistency in your life.

What do you cling to when you feel stuck? What are you passionate about? What do you run to when you celebrate?

Filters will emerge from these variables that help you see where your biases lie. In some instances, our hidden biases are only realized after a statement is made, which invites the opportunity to self-reflect and question why something was said.

3. Identify the potential of your biases

Sometimes, our hidden biases open up new avenues in conversation making for a brilliant dinner table discussion. They broaden our viewpoint.

Bring your biases to the conversation and see where it goes, for example: “I am aware that I was raised with a typically patriarchal view of family, so this influences my contribution to the conversation around marriage, maternity leave and family.”

Be aware of the potential of your biases, and be aware of their biases too by asking yourself questions like: What factors influence how they responded to that situation?’ How would I respond if I were in their position?

4. Focus on the individual

Crucially, engage with the person in front of you on a human level. Name, status, upbringing, nationality and class aside, connect over humanity and shared experiences you may have.

Are there any hidden biases of your own that you have discovered? How are you learning to address them?

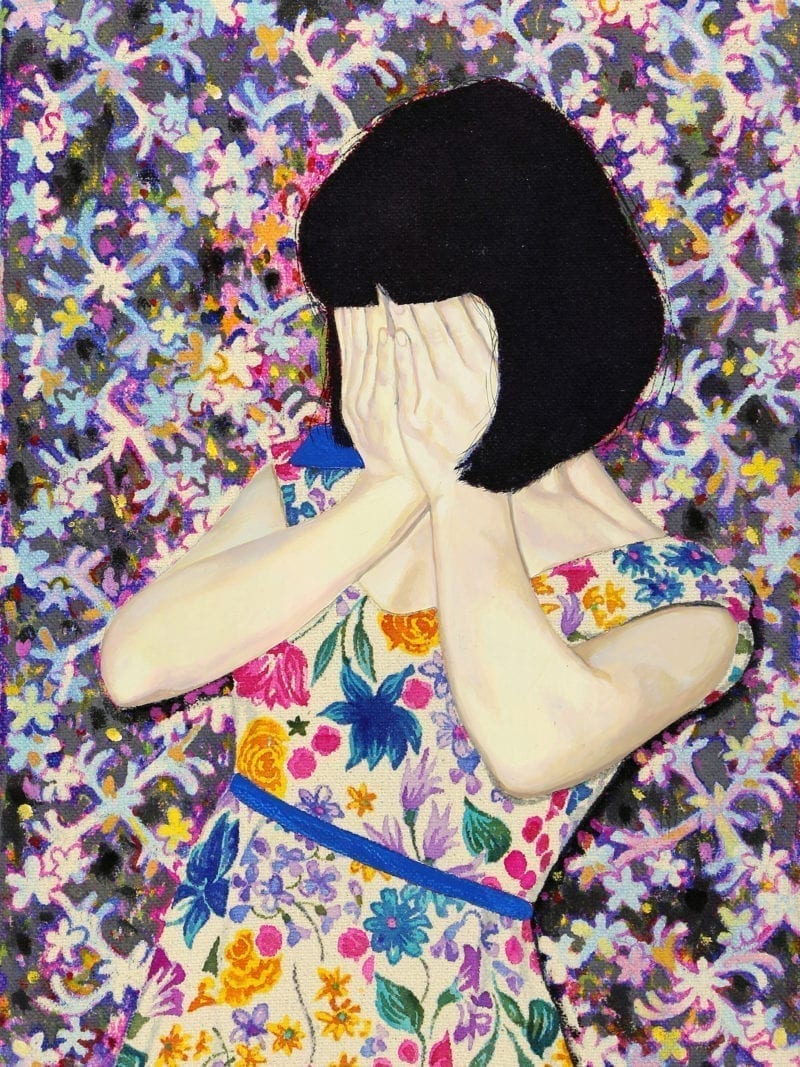

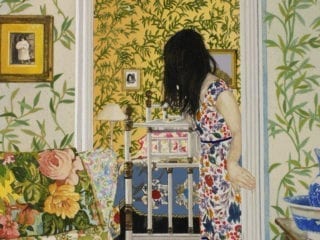

Image via Naomi Okubo, Darling Issue No. 17

4 comments

I love this! So important to realize the difference between racism and bias. We all have bias, but as a white female myself, I was a little disappointed by the sentence, “ While people might like to think that they are not susceptible to these biases.” Isn’t that a bias sentence in itself? I think many people like to think they aren’t biased regardless of their race or gender. That’s the whole point of the article! We are ALL susceptible to it and that’s why we have to be careful. So why make this a white people issue?

Hey Melanie – thanks for feeding back! The part you quoted is not talking about race or *white* people at all. My belief and point here is simply that biases are a standard part of human life regardless of ethnicity, race or gender, and are not necessarily always discriminatory. It could be that you misread it – happy to chat more though!

Oh, I definitely have some hidden biases – I’ve been trying to address them more lately. Great post!

–

Charmaine Ng | Architecture & Lifestyle Blog

https://charmainenyw.com

Thanks!