Cecilia (Ceci) Sibony is a peace activist and social entrepreneur who spent seven years in Israel and Palestine building relationships with individuals and organizations on both sides. With her MA in Negotiation and Conflict Resolution and Non-Profit Management from the Fletcher School at Tufts University, focusing on how to improve the effectiveness of peace-building initiatives, Sibony learned methods of conflict resolution, social entrepreneurship and organizing which led her to her current venture.

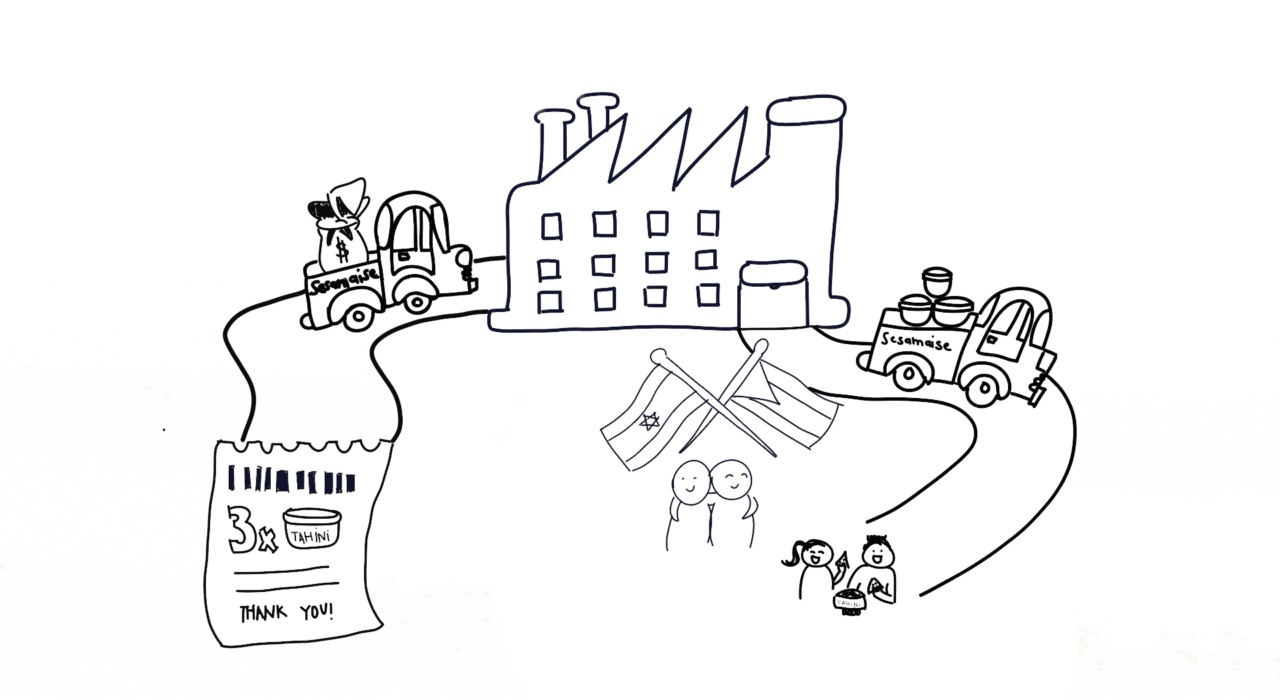

Since 2016, Ceci has been building Sesamaise Tahini, a social food business with a sustainable, scalable and collaborative supply chain in Israel-Palestine. I recently interviewed Sibony on her work and the ongoing conflict. What she shared was both fascinating and inspiring.

Read on for her story:

Beth Doane: Where did your passion for peace-building, specifically between Israelis and Palestinians, come from?

Cecilia Sibony: When I was 4 years old and the First Intifada started, instead of playing outside with the rest of my cousins, I sat in the living room with my conservative Israeli family in Maryland, watching the violence committed by both sides. I asked my dad, “Aba, why do people fight if peace makes you happy?” My commitment to and passion for Israeli-Palestinian peace-building was born in that naïve and painful moment.

Over the years it grew, especially as I wrestled with my strong familial and communal connection to Israel and the atrocities stemming from the Occupation of Palestinians; the latter of which did not sit well with my Jewish upbringing, focused on social justice and preventing genocides like the Holocaust. I wanted Israelis to live in peace and prosperity in a Jewish homeland, and I thought Palestinians deserved that as well, and the only way to make that happen was through an end to the Occupation and a real peace.

BD: What does a successful resolution look like, from your perspective?

CS: I believe a truly successful resolution will have to start from the grassroots. Negotiated, top-down, political agreements tend to fall apart easily as soon as violence occurs, especially if there isn’t a strong base of mainstream Israelis and Palestinians that support one another and the negotiated agreement. Unfortunately, we are a long way away from that. Systematic segregation between Israeli Jewish and Palestinian communities makes building constructive, empathetic relationships with the “other” nearly impossible right now; however, there are dozens (if not hundreds) of organizations and businesses on both sides of the Green Line (the demarcation line set out in the 1949 Armistice Agreements between the armies of Israel and those of its neighbors after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War) that facilitate this kind of relationship-building. The challenge is doing it at scale and reversing the tide of hatred and mistrust.

In terms of a successful political resolution (one-state vs two-state etc.), I believe that once the grassroots infrastructure is in place to support a political resolution, figuring out the strategy and details will be more straightforward and sustainable. I don’t pretend to know what the geopolitical and socio-political landscape will look like then, so I do not like to speculate on that.

BD: What are some of the biggest challenges facing organizations trying to make peace in intractable conflicts?

CS: So many. The idea of not just “preaching to the choir” stands out the most. Most of these peace-building organizations offer programming that like-minded Israelis and Palestinians opt-in to. Trying to change hearts and minds of those who don’t already believe in peace through programs that create empathy, trust and understanding with facilitated dialogues is more of a challenge, however. Actually, increasing swaths of mainstream Israelis and Palestinians view this kind of work as extremist, naïve and betraying each groups’ national cause (ie. laws restricting their work in Israel and the anti-normalization movement in Palestine).

Also, the many non-profit organizations in this space, which have similar visions and objectives albeit different strategies, rely on the same pool of donor funding; therefore, they actually compete with one another to “stay in business,” making broad-based coalition- and movement-building and cooperation between these organizations difficult. This also makes innovation and outside-the-box thinking hard, not only because of inertia, but also because these organizations are incentivized to build programs that fit within the prescribed boxes of these donors.

I wanted Israelis to live in peace and prosperity in a Jewish homeland, and I thought Palestinians deserved that as well, and the only way to make that happen was through an end to the Occupation and a real peace.

BD: Have you found that there has been an increase, specifically in younger generations, of creative or unique ways to unite different groups?

CS: Yes and no. There are some exciting, market- and business-based approaches that have been operating discreetly in the last couple of years. It’s almost like business is the last domain where it is acceptable to do this kind of work. My friend, Forsan Hussein, and his Israeli Jewish partner, Ami Dror, have the first and only Israeli-Palestinian VC called Zaitoun Ventures, funding joint businesses and those with a strong diversity component. On the other hand, and sadly, in the established organizations that have been doing this work for decades, I have seen (and experienced myself) resistance on innovative approaches.

BD: Why tahini? Why did you choose it as the vehicle for the business and what business opportunities/unmet needs did you identify that it could solve?

CS: I think tahini is one of the most under-rated, under-utilized and misunderstood ingredients in the American cooking repertoire. True, Americans now know what it is because of hummus, but in the Middle East and many other parts of the world, they put it on and in everything (way more than hummus!).

When I moved back to the US, I couldn’t understand why tahini wasn’t a “thing” here, until I tasted the tahini found in the US market. Plain and simple, they didn’t taste good, and I knew that Israelis AND Palestinians make some of the best tahini in the world and it was one of few things they actually share. This presented a serious competitive advantage and market opportunity. For health reasons, American food trends are in plant-based whole food made with few, clean, and simple ingredients, while Americans are snacking more than ever (versus eating meals) and cooking less than ever before. I hear it all the time in the farmers market: “I’m trying to be more plant-based but I’m hungry and don’t have time to cook.”

When high quality, authentic tahini is mixed with liquids, as we do with our tahini dips, it makes a beautifully creamy, filling, nutrient-dense dipping sauce that you can use in a thousand ways to make easy, quick, and delicious food (ie. as a sauce, spread, dressing, dip, condiment, topping for a grain bowl and more). There’s no other product in the supermarket’s sauce/condiment/dressing/dip section that is as clean label, versatile, nutrient-packed and delicious; there’s a reason humans have been eating sesame seeds for 7,000 years!

BD: What challenges have you faced being a young female founder in societies known for being quite patriarchal?

CS: Even though I didn’t have a product, company or sales when I first started vetting tahini companies in Israel and the West Bank, I definitely felt like most of the owners I met with did not take me seriously. Food businesses in Israel and Palestine are mostly male-dominated and passed down in families, so I was an outsider in every sense; I was a young woman and had never worked in food. I understand why they did not take me seriously considering how early-stage I was at the time, but I do always wonder if I was an older man with a business idea, how would they have responded?

I turned this challenge into an opportunity, though! I kept looking and meeting with different companies until I found 2-3 that were supportive, and I’ve worked since 2016 to build relationships with them. The next phase of the company is fundraising.

BD: Where are you at currently with the company and its peace-building efforts?

CS: We just finished up our #tahinitogether crowdfunding campaign on March 23rd. While we didn’t reach our ambitious funding goal, which would have given us the pre-orders we need to distribute nationally and add more Israeli and Palestinian family businesses to our supply chain, we built a lot of buzz and excitement around tahini and our mission and partnerships with amazing organizations and people.

Now, we are looking to use that momentum to raise money more traditionally. I know that is not easy, especially as a female founder of a social-change business, so if any Darling readers out there have advice, connections or money to invest, reach out to me personally! I’d love to chat (info [at] sesamaise.com) about how we can make REAL FOOD for REAL CHANGE in the US and Middle East.

Images via Sesamaise Tahini