“He has your eyes,” the nurse said, smiling fondly as she placed my freshly bundled newborn son, James, back into my arms in the hospital delivery room. I beamed, pride swelling within me. I was secretly hoping he would.

My eyes have always been my favorite physical feature. Growing up, I did not escape the common body insecurities that often plague young women, but I always felt proud of my eyes. I loved that I shared them with my dad, blue and kind. I loved that they disappeared into my smile. As I watched my baby grow, cherishing every milestone and enjoying the connection between the two of us, I marveled at seeing his eyes sparkle blue and loved the way they formed tiny crescents when he smiled and giggled.

Strangers often commented on our resemblance. “He has your eyes,” they would say. Once again, my heart would swell full. After several miscarriages and months of infertility, I wondered if I would get to experience what it feels like to see parts of yourself reflected in a tiny human that you love so much. Miraculously, here he was and he had my eyes.

I wondered if I would get to experience what it feels like to see parts of yourself reflected in a tiny human that you love so much.

Six months into his fresh new life, we sat in the doctor’s office, waiting for his scheduled check-up. It was news to me that a routine eye exam would be part of this appointment. I tried to remain calm, but I found it difficult to relax as James stared at a screen with probes on his head. I tried to read encouragement on the technician’s face, but I couldn’t find it.

“It might be nothing, but it appears that one eye is working harder than the other. He failed his vision test,” she said about as casually as she would if she was telling me about the kind of sandwich she ate for lunch.

I stared at her as shame washed over me and my heart went double-time with fear. He has my eyes.

I stared at her as shame washed over me and my heart went double-time with fear. He has my eyes.

You see, while I have always loved the way my eyes look, I have struggled to accept the way they function. I have had extremely poor vision ever since I can remember, but it was not until I tried to learn to read that others became aware that something was not right.

I did everything I could to avoid having to wear glasses. During routine eye exams, I would quickly memorize the vision chart in order to get the answers correct. For better or for worse, my mind was much sharper than my vision.

My first grade teacher was the first one to suggest glasses. Squinting at the blackboard from my seat in the front row gave me away. As if being the new girl at my school wasn’t enough, I now had to wear these enormous magnifying glasses that never seemed to stay in the right spot on the bridge of my narrow nose. Others’ reactions to my new look made me feel ugly and led me to understand that the glasses made it difficult for people to really see me.

How was it possible that an accessory that was supposed to help me see, made it difficult for people to see me? How could it be that my glasses made me feel invisible and exposed at the same time?

At age 6, my poor vision and the glasses that followed became my particular symbol of rejection, shame and a lack of belonging. While I knew that vision problems were minor in comparison to other hardships many children and parents endure, I desperately wanted to protect my son from the feelings I felt as a result of my own vision impairment. It wasn’t his vision or even the possibility of James having to wear glasses that I was afraid of. At the heart of my pain was the fear that my son would struggle to see himself the way I see him.

At the heart of my pain was the fear that my son would struggle to see himself the way I see him.

As I held him in the doctor’s office, his squishy body relaxing into my own, I reminded myself that there was no news the doctors could give me that would change the eyes and heart I had for James. Part of the honor of being his mama is teaching him to love himself in the same way.

I was thrilled when his eyes looked like mine. I was worried when we learned that his eyes likely function like mine. Now, I’ve found myself hoping and praying that my son would have eyes to see himself the way I see him and the way I was learning to see myself: lovable, worthy, unique.

It took me a long time to learn to see—to stare down my inadequacies, look at my weaknesses and see the value and worth in the midst of what I wish was different. Glasses were just the beginning. Life gave me many opportunities to practice, and I’m quite sure I’m not done practicing this important skill. While I still struggle often, with time, I have learned to see value in myself regardless of what others might see in me at a given time.

My son may have poor vision. My hope for him, beyond his vision, is that he would learn to see the value in who he is outside of his circumstances. He has my eyes. May he share the eyes I will always have for him.

What is your hope for your children or future children? What is something that you’d like to pass on to your kids?

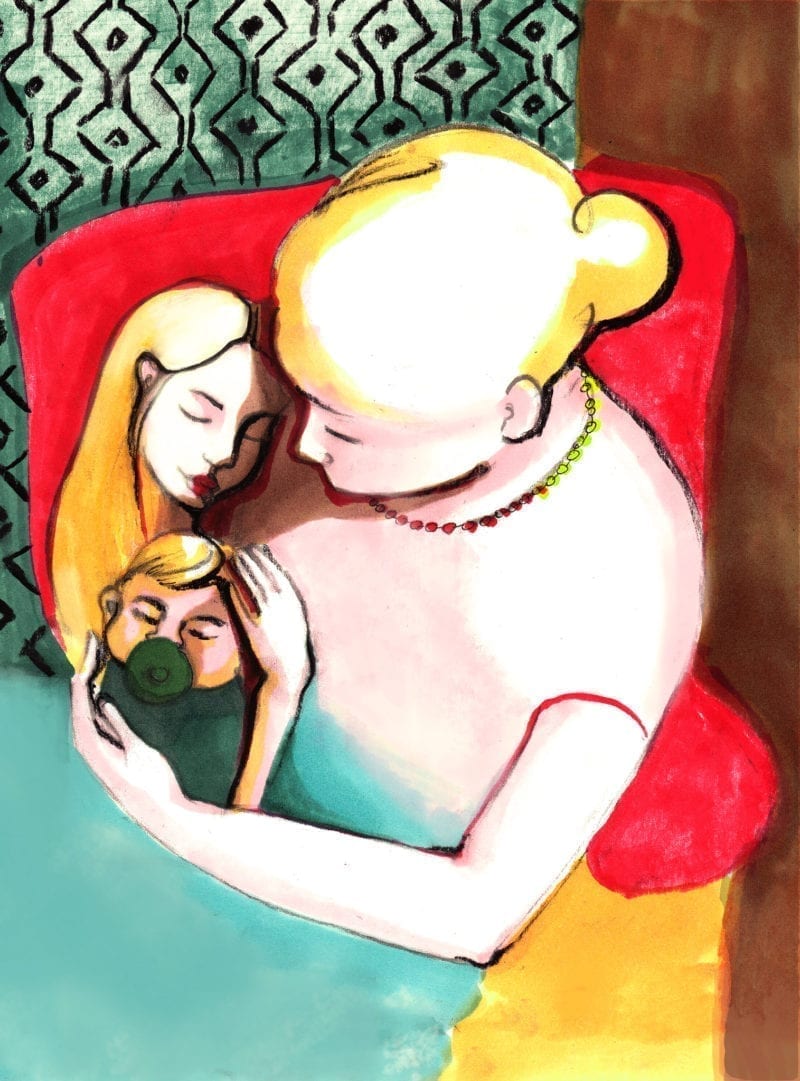

Image via Karolina Maszkiewicz, Darling Issue No. 16