At Darling, we are passionate about cultural, environmental and social issues impacting women and girls. “Nonprofit Spotlight” shines a light on nonprofits that are doing impactful work on the ground level. Each month, we will spotlight a charitable organization in order to educate and encourage advocacy and action.

When it comes to the global crisis of human trafficking, The Human Trafficking Institute is cutting straight to the root of the problem by empowering police and prosecutors to stop traffickers. The nonprofit works inside criminal justice systems to provide world-class training, investigative resources and evidence-based research necessary to free victims.

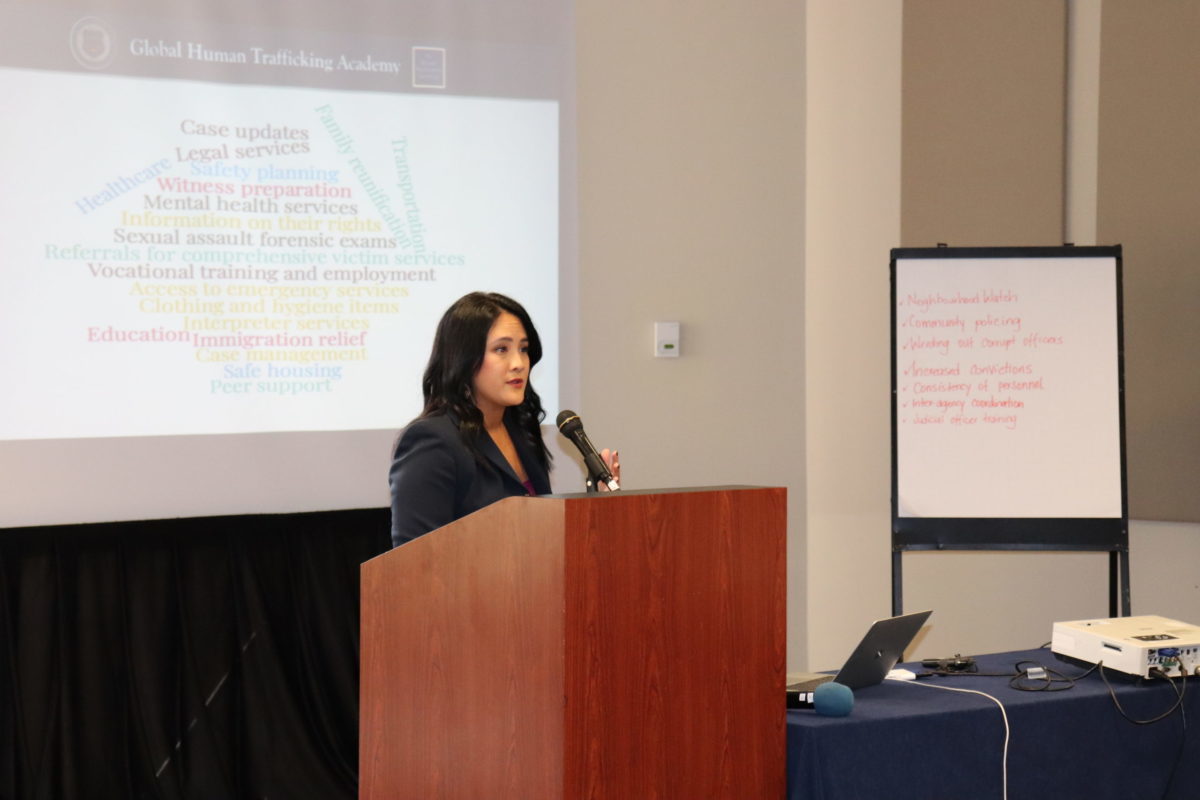

As the Director of Victim Services, Marie Martinez Israelite is at the helm of leading the institute’s efforts related to victimization issues. She and her team focus on creating support systems based on trauma-informed practices that prioritize meeting the needs of victims. Combining her passion and experience in social work and social policy, Marie works day in and day out with justice system partners to employ these approaches that empower victims to have a voice.

“I can’t tell you how many times over the course of the last 15 years that I’ve been doing this work when I will have a moment where I say to myself, ‘I cannot believe I get to do this as my job,'” Marie said. “It’s just really gratifying and challenging. I am very fortunate.”

Darling got to chat with Marie about her role at The Human Trafficking Institute and how the nonprofit works with criminal justice professionals to create trauma-informed, victim-centered approaches to meet the needs of survivors at all stages of their journeys.

Tell us about how you got involved with the issue of human trafficking and how your career in this field took shape.

I was really fortunate to find an interesting niche within human trafficking early in my career. It was during my second year at the University of Pennsylvania in grad school, and I had a practicum at an agency called HIAS Philadelphia that provides legal and social services to immigrants, refugees and political asylees.

I became really interested in working within and helping immigrant communities. I saw the frequency with which immigrants become victims of crime, all of the barriers they face and the difficulties to access not only immigration relief, but also a wide range of services, support and housing that are critical for thriving in a new country.

I moved to D.C. after finishing grad school for a post-grad fellowship and landed at an amazing office called the Office for Victims of Crime at the U.S. Department of Justice. It was just really lucky timing for me because that was the time when the DOJ received its first Congressional appropriation to fund victim services for trafficking survivors who were exploited in the United States. At that time, most people thought of trafficking as something that only happened elsewhere, but what service providers, advocates, attorneys and investigators were really seeing was there was this tremendous need for services for victims who were exploited in urban, rural and suburban communities right here in the U.S.

After a number of years at the Office for Victims of Crime, a mentor from the Department of Homeland Security in Homeland Security Investigations reached out to me. She was charged with developing a program to serve trafficking victims who were identified in the course of DHS investigations. She asked if I would be interested in doing what we call systems-based advocacy, which is more operational work, training and creating policies for criminal investigators on everything from immigration relief to how to work effectively with NGO partners. We knew that services were critical for victim restoration and for the success of the case. They needed advocates within the system who understood why these services are so critical, what it means to be victim-centered and trauma-informed and how you put those concepts into practice when you’re investigating a case and when you’re interviewing a victim.

I was a Trafficking Victim Specialist there and then went on to become the Chief of the Victim Assistance Program, which was really a chance to build a responsive victim-assistance program where none previously existed within this federal law enforcement agency. Later, I worked for a consulting firm called ICF. The biggest project I worked on there was facilitating the work of the U.S. Advisory Council on Human Trafficking, which is a presidentially-appointed group of trafficking survivors who advise the federal agencies on their anti-trafficking efforts. That was a really great chance to learn from people who have lived experience. Most recently, I was invited to join the team at the Human Trafficking Institute. I reached my two-year anniversary last month.

Happy anniversary! Can you tell us about the Human Trafficking Institute and your role there?

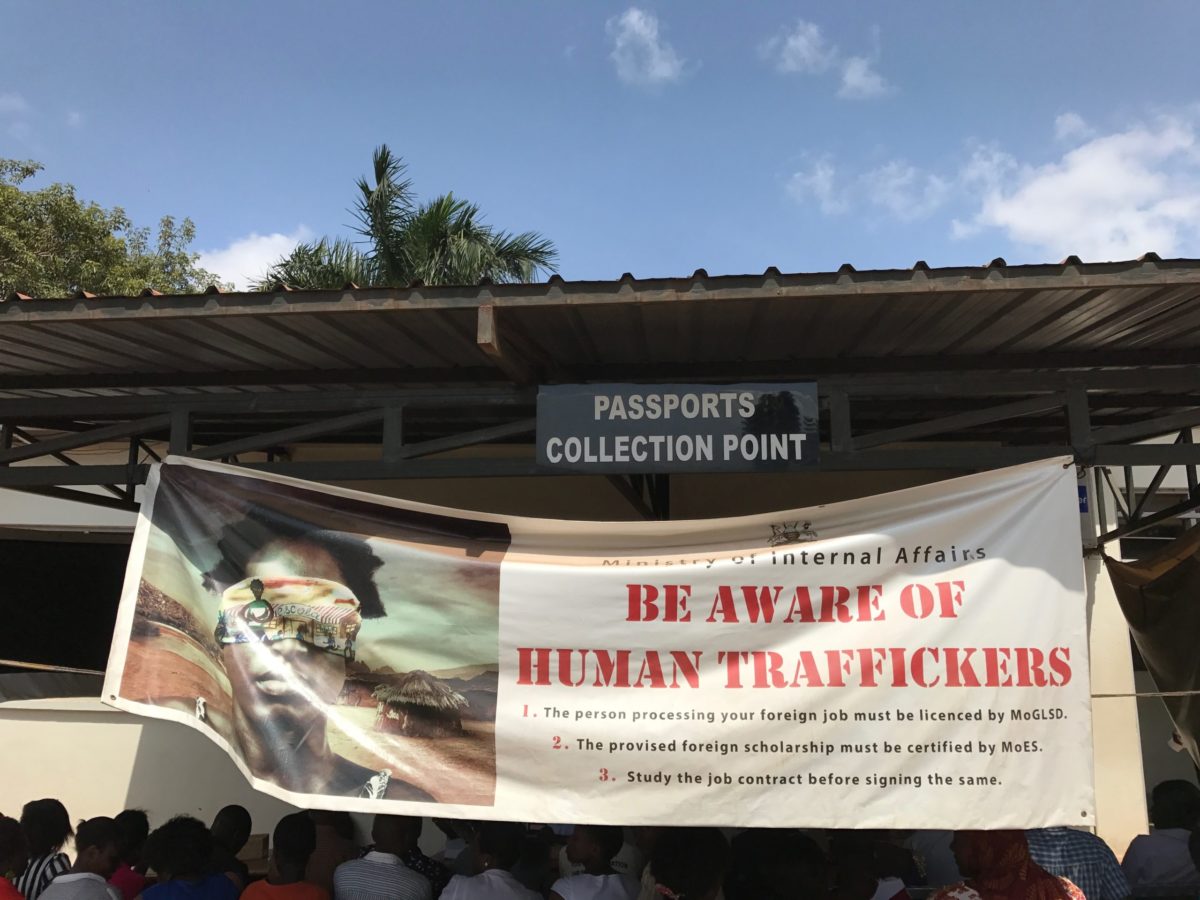

The Human Trafficking Institute is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit. We’re unique in the nonprofit space in that our focus is on combating trafficking by focusing on stopping traffickers. We do this by developing more robust criminal justice efforts to stop traffickers, interrupting the cycle of victimization and creating deterrents to engaging in trafficking related crimes. We work closely and long-term in a few countries at a time to build their justice systems’ capacities to not only recognize trafficking, but to also effectively investigate and prosecute cases and hold traffickers accountable for their crimes. We work in places where, historically, investigations and prosecutions of traffickers have been infrequent and not representative of the problem of trafficking in the country or in the local community.

We work in places where, historically, investigations and prosecutions of traffickers have been infrequent and not representative of the problem of trafficking.

We also have a world-class team that provides ongoing training, guidance and capacity-building support for our partners. We work side-by-side with investigators and prosecutors in the countries in which we work. We also help to foster more meaningful and effective partnerships with service providers who are working on the ground and help our criminal justice partners understand how to utilize those systems, make referrals and work to really help get victims the holistic support that they need.

As the Director of Victims Services, my job is mainly to lead the institute’s efforts with our partner countries on all issues related to building better support for survivors at all stages of their journeys. I’m part of the operations team that develops and leads training for our partners and my focus is really giving them a sound foundation of trauma-informed, victim-centered approaches and what that looks like in the context of the criminal justice system. I help our partners think through operational considerations for victims and plan more effectively for victims who will be identified in the course of their investigative work.

I also help with problem solving around victim-witness challenges (factors related to victims’ experiences in their role as witnesses to the crimes committed against them). Victims don’t come to the criminal justice system by choice but because of what happened to them, and they don’t make ready witnesses. There’s a lot of things about trauma that make it very difficult for victims to testify and to cooperate with the various stages of being a witness in a criminal case.

Can you share some of the typical experiences for a victim in a trafficking case?

This is challenging because there is no “typical” in a trafficking case. Trafficking can happen to anyone in any range of labor or commercial sex situations, but the common thread is that traffickers exploit vulnerability. Men and women who are desperate to provide for their families, migrants who are coming to a new country and struggling to make a better life or children and teens who are marginalized. They might be fleeing unstable or unsafe homes or even seeking approval and belonging.

Trafficking can happen to anyone in any range of labor or commercial sex situations, but the common thread is that traffickers exploit vulnerability.

Traffickers employ a wide range of tactics. They are great at reading the vulnerabilities and needs of their intended victims to “seduce” (in both a sex trafficking context and a labor trafficking context) and to control them. It’s not always by physical force.

More than physical force or bodily harm, the common tools of coercion and control are deception, fraud, emotional manipulation and psychological coercion. It’s threats against their family members and against loved ones. It’s document servitude for immigrant victims, a withholding of their legal documents.

Victims can be identified in a range of ways. We’ve seen “good samaritan” reports—a concerned neighbor, business patron or community member who comes forward about something that doesn’t seem right. Health care providers, like HEAL Trafficking, build expertise to be able to recognize and effectively respond to trafficking in the context of their day-to-day work. When someone presents with suspicious injuries or there is suspicious behavior from someone who’s accompanying them at an appointment or at the hospital, that might be indicative of trafficking.

Service providers make a lot of referrals. Many times victims are not “rescued,” but identified months or even years after they’re out of their trafficking situation, which is more common than I think most people realize. They may not have known that they were victims or that what happened to them during their exploitation is called human trafficking. For immigrant survivors, they usually don’t know the rights they have in the United States. So it’s very rare for victims to self-identify as victims.

When you say a “victim-centric approach” to working in the court system, can you share some examples of what you might advise a law enforcement group to do?

It really starts with a true and deep multidisciplinary teamwork with NGOs in a way that is open, trusting, transparent and where the investigative agency, the prosecutor and the service providers are working in advance to anticipate what the needs are going to be. It’s also about transparency and giving service providers as much information as possible so that they can prepare.

There’s no “one-stop shop” for trafficking victim services. Even the leading victim service providers are probably going to have to work with several other service providers to meet the range of needs that trafficking victims might have. It’s also imperative to make sure that you don’t put the full burden of the case’s outcome on the victim.

You have to build your case in a way that you’re developing complete evidence that will corroborate a victim’s story. The vast majority of the time, a trafficking survivor (whether it’s a child or an adult) coming out of sustained trauma is not going to be able or ready to speak to law enforcement in the immediate aftermath of being identified. There’s a lot of trust that needs to be built. There are a lot of fears that survivors have of people in positions of authority and of law enforcement.

There are a lot of fears that survivors have of people in positions of authority and of law enforcement.

One of the things that I always suggest is to prioritize the victim’s safety. Find out what their immediate needs are as they identify them. Make sure they’re being connected to service providers for intensive case management: for housing, medical care, mental health services and services for their children. Postpone the date of a longer, more in-depth interview to a time when the victim is rested, when they’ve had a chance to eat and after they’ve been able to meet with service providers. Empower them with choice and a voice as much as possible.

Service providers often offer neutral, safe and confidential locations for interviews. There are a lot of ways to ensure confidentiality and safety without necessarily bringing someone into a police station. Letting them choose, if you can, the time of day they want to be interviewed, where they want to be interviewed and if they can be accompanied by an advocate who can wait for them during the course of the interview. Go through expectations and ground rules for the interview. Build rapport and don’t immediately go into the details of the trafficking victimization.

What’s the goal for these interviews in terms of law enforcement? What are they trying to do when they’re talking to these victims?

The first goal is to obtain victim statements in their own words about what happened to them in the course of their trafficking victimization. The end goal is to be able to hold traffickers accountable for their crimes—to be able to successfully investigate, prosecute and sentence the trafficker.

Law enforcement is trying to find out what happened. They’re trying to ascertain that the crime occurred and how it occurred. During the interview, they’re trying to get a timeline, of course, but they’re really, at the heart of it, trying to get the story of what happened from the victim in their own words.

In the event that a victim is found and law enforcement is going after that particular trafficker to try to hold them accountable for their crime, how does that unfold?

It is important for people to know that it’s possible to be victimized and re-victimized by the same trafficker, return to a trafficker or become victimized by another trafficker before they actually end up becoming fully free. They may become aware that there’s a service provider who can provide assistance with housing, support, case management and individual and group counseling.

Sometimes, when survivors aren’t quite ready to leave a situation or are too fearful to leave a situation, it’s not always a straight path to freedom. You might see some survivors who end up being identified, but then go back or they end up re-victimized. In other times, when they’re ready to engage with services, they would engage with a case manager at a trafficking victim service provider who can do safety assessments and work from a victim-centered and person-centered approach.

There’s no template for how you provide services to a trafficking survivor because every trafficking survivor is unique and different. They have different strengths, vulnerabilities and concerns. Trafficking victim service providers really work to develop the case management plan based on what the survivor’s greatest needs and concerns are.

There’s no template for how you provide services to a trafficking survivor because every trafficking survivor is unique and different.

One of the things that we know is that criminal cases take many months, usually years, to resolve from inception all the way through trial and sentencing. There are often a number of times that a victim will be interviewed. Victims are asked to do many hard things in their role as witnesses such as revisit the role of the crime scene or review physical evidence related to their trafficking. Ultimately, the goal is helping victims to participate fully while not re-traumatizing them.

You mentioned earlier that you had one job that you acquired through a mentor. How would you advise women early in their careers? How do they develop a good relationship with a mentor?

Every workplace has an inspiring woman, an inspiring mentor doing the work. My advice for young women is to go about building that relationship from a humble place. Watch, listen and learn. See how they relate to other people. See how they’re able to build influence, respect and trust and what’s actually effective in their leadership.

My advice for young women is to go about building that relationship from a humble place.

Also, I was willing to do any type of work when it was asked of me. It wasn’t always the exciting, thrilling, deep, challenging or substantive work when you’re still pretty junior and new to the field. I think that people who are willing to work hard and do it all, do themselves a service. You demonstrate that you’re a team player who can be relied upon. People in positions to mentor you will take note of that and give you opportunities.

The really wonderful thing about the anti-trafficking movement right now is how much it’s grown and the space for professionals to make different types of contributions. There’s no one path. You can make a difference in anti-trafficking if you’re a health provider, an educator, a law-enforcement officer, a victim advocate, a grassroots community organizer or a volunteer.

If people are looking for resources to learn more about human trafficking, what resources would you recommend?

Some of the places that I would recommend that people visit and educate themselves through are: the Human Trafficking Institute, Trafficking Matters, Polaris, Love146, HEAL Trafficking, ECPAT International, The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children, Freedom Network USA, Free the Slaves, The Coalition of Immokalee Workers, Verité, The Freedom Fund, The Human Trafficking Legal Center and Coalition to Abolish Slavery and Trafficking.

I also think it’s really important to follow the work of survivor leaders. Many survivors have become advocates and activists in their own right. The National Survivor Network is one place to learn about their work. Connect with and hear from survivors who may be available to do trainings or consult on projects.

The U.S. Advisory on Human Trafficking is a presidentially-appointed council of human trafficking survivors who advise government efforts. Internationally, I would recommend that people look to the International Organization for Migration, World Relief, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, International Labor Organization and the International Justice Mission. These are great places to start.

What are ways Darling readers can get involved in the human trafficking space?

Everyone can contribute by being more conscious of the choices that they make as consumers. Know the power of your consumer power and demand accountability in supply chains from the companies that you support with your purchases.

Readers can use tools like The Responsible Sourcing Tool to find out about human trafficking and supply chains. You can even use certain apps to learn how to be an impactful and informed consumer. The Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB) has an app called Sweat and Toil. It allows you to browse by category all the goods that are known to be produced with child labor, forced labor (or both child labor and forced labor) and see what governments are doing to eliminate those practices. Their website also publishes a list of goods and their source countries produced by child labor and/or forced labor.

On a very basic level, we can do a lot to combat trafficking by educating ourselves and avoiding sensationalism. I wish I could underscore this—only share sourced and reliable information on social media about trafficking. Think critically when you see posts about sex trafficking in particular on social media. Is it a trusted source? Where is it coming from?

I wish I could underscore this—only share sourced and reliable information on social media about trafficking.

It’s also important for us to model the language we use and the attitudes that we take so that we are always supporting survivors and minimizing re-traumatization. You never know who is a survivor, what trauma someone has been through in your own community. You may not know they’re a survivor.

Be the person who jumps in to correct someone if they say “child prostitutes.” There’s no such thing; children do not have agency and can’t consent to commercial sex. A minor who is involved in sex for money or sex in exchange for anything of value is a victim of trafficking. We should all check our own biases about “good victims” and “bad victims.”

Readers can also go to the National Human Trafficking Hotline, operated by Polaris, to request additional information about trafficking or to report suspected trafficking. They can also subscribe to updates from Trafficking Matters, where they can access resources about everything from trending trafficking cases to breaking domestic and international news, to reports from government and non-government agencies.

How can Darling readers support the work of the Human Trafficking Institute?

We have a wonderful program called Justice Partners, which enables donors to give recurring monthly donations in amounts as small as $25 for our work. The idea is that even at smaller amounts, sustained donations by a community of engaged, committed individuals helps to generate collective action and sustains our strategic work.

The great news is that it’s also a two-way relationship. While supporting our work, Justice Partners get monthly progress updates from the team, access to special institute events and also resources and ideas for high impact advocacy in their own communities.

To learn more about the Human Trafficking Institute, follow them on Instagram. Also, visit their website to donate and combat slavery at its source by empowering justice systems to stop traffickers!

Is there a nonprofit that is doing important work to support and empower women and girls? Leave a comment below to let us know who to feature next!

Images via Human Trafficking Institute