When the clock struck 11:59 p.m. on December 31 ushering in the New Year, I held my breath. With my eyes squeezed closed, I exhaled and glanced at the clock—it was 2019 and this year held the 10-year anniversary of my mother’s death. Months ago I had thought about this moment, and wondered if this would be the first thing I thought about in the early days of 2019.

Sure enough, it was and I didn’t even make it to 12:05 a.m.

On the day I lost her, the May sun was bright and the roses that lined our home’s front porch permeated the spring air with a sweet fragrance. 17 is a selfish age, and rarely did I consider a life aside from my own. She was sick for more than five years, and I didn’t see it coming. I charged willfully toward the future, making plans for college and beyond so meticulously that I didn’t realize when your mom has cancer for five years, she may be absent from the dinner table sooner than you thought.

The Monday after the funeral, I returned to school. My Vans skimmed the dew off the grass as I cut across the yard to my car. Our neighbor was backing his car out of the garage. Sprinklers sputtered in the distance, dowsing rows of perfect suburban lawns. There wasn’t a cloud in the 7 a.m. sky.

Our small piece of the world moved on without even a stall. I stared down the quiet neighborhood street in disbelief. I don’t think I have ever felt so small.

Before that day in May, very little had gone wrong for me. Sure, my mother had maintained a strict appointment to have chemicals dripped into her body most Friday afternoons since I was 11, but even then—I had lived a privileged childhood.

Summers consisted of road trips and weeklong camping excursions. Visits to San Francisco and Los Angeles included stops at museums and art galleries. She eagerly nudged my brother and I in the direction of becoming asset-to-society adults, even if she would not be around to see it.

Our instincts often tell us to run. It’s emotions that convince us to stay. It was an easy decision to run after high school—my instincts, mind and heart all told me to do so.

I had been hallucinating, I was sure of it. At Safeway I saw her. Driving to school I saw her. In our neighborhood, I saw her the most. She would shuffle down the street on a winter evening; our Labrador’s tail wagging like a metronome beside her. I couldn’t take my eyes off her, the distance lessening between us. Then, she would walk by and her eyes weren’t the right color and the dog would be too fat.

I spent senior year of high school telling telemarketers she couldn’t come to the phone. It was time to run. In my 20s, sometimes I would see mothers and daughters caught together in a shared moment. The sight of a mother and daughter keeled over in a fit of laughter at a restaurant could stop me in my tracks.

It would strike me so deeply that it was nearly an out-of-body experience. An ordinary moment, soured with memories in an instant. I found myself wondering if it would ever stop happening.

The tenth year hurt, and it hurt that it was hard. There was a sense I had recovered, moved on and people were proud of me—it’s a narrative I’ve told myself and others have told me. In the months leading up to the anniversary, I felt like I was slipping, relapsing into a grief that I had not felt for a decade.

At 27, the grief has context. A decade of life and growth had informed what I thought I knew about loss. In the tenth year, context shoved grief back to the forefront of my life and demanded to be acknowledged and assessed—apparently I didn’t do a proper job of that while I was carrying around an SAT practice test book at 17.

So, does time heal grief? My first instinct is to say no, it doesn’t. If it did, then I would not have been thinking about my mother in the early morning hours of January 1. Time passes, and grief shifts. More than heal, you acclimate. Begin to make friends with the absence.

In the summer, I found a picture of her that I had never seen before. She’s in her early 30s posing next to her new car on a hillside road in southern California.

I don’t know if time heals grief, but I do know that it enlightens it. It no longer devastates me to find pieces of her, and they say nothing to me of her absence. Instead, they are magical reminders of her existence.

How have you learned to process grief? What has loss taught you about life?

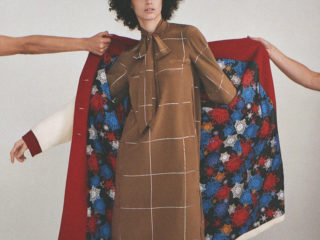

Images via Stephanie Williams, Darling Issue 13

2 comments

This year marked 10 years of my mom being gone as well. I was 18 when she died. I don’t know if it’s the amount, 10, or the maturity but in the last couple years grief has asked for my attention again.

Thanks for sharing!

This is such a beautiful and inspiring piece. Really felt the raw emotions from your words. Thanks for sharing!

–

Charmaine Ng | Architecture & Lifestyle Blog

https://charmainenyw.com